By Eliana Fulton

Introduction: A Bit of a Disclaimer

In the early days of fiddling around with ChatGPT, I once asked AI to rewrite a sample passage as if Amy Tan had written it. The result was a soulless amalgamation of metaphors she had used in previous works thrown together into mediocre mush. Although it was cool that the AI could make something with an aftertaste of such a fantastic writer, I would’ve rather reread “Fish Cheeks” or The Joy Luck Club. Only a human being can conjure up a world through art that is vivid and real enough to feel as though you are seeing it through their eyes. That is my disclaimer for why this post focuses on using AI as a tool for advancement and efficacy and not for large scale generation.

Last year I personally wrote a more extensive analysis of AI’s role in the publishing field at large, and YellowBird’s founder, Sara Kocek, provided a very insightful interview. One comment she made that really stuck with me was:

“What makes writing good is that it reminds us what it is to be human, and right now, AI can’t do that.”

Since then AI technology has advanced, and the broad conversation on how people in the publishing industry might use it has increased. While ChatGPT still can’t write with the emotion that a human being can, it gets a lot more convincing with every update. In fact, there is a social media trend of comparing the outrageous and easily spotted AI videos from a year ago to the scarily convincing deep fakes that are not circling the internet.

Don’t fret. AI is not going to replace creative minds any time soon because 1) AI can never be as inventive as real people who are influenced by their unique cultures and experiences and 2) there have been enough adverse reactions to the “uncanny valley” feel of AI to keep it from mainstream media.

In every evolving industry, successful people need to adapt to changes, and publishing is no different. By keeping an eye on the standard that larger publishing houses set for their editors and writers, those looking to publish in the future can stay ahead of the game. For example, Yellow Bird Editors do not submit unpublished works from clients into public AI chats to prevent risk of copyright infringement. Copyrighting literature from AI’s training programs is already a firm standard Penguin Random House has put forward.

Many people in creative fields are scared of AI, and while I would personally prefer that we aim to use human creativity, it’s becoming an important part of this field. If we ignore it disdainfully, it will overwhelm us in the near future, so we should learn how to manage it as a tool.

Things to consider before using AI

AI is using other people’s recycled ideas, so remember that you are already 100 times more creative than it is.

Every 20-50 queries you submit to a chatbot costs data centers about 500 ml of fresh water to cool down their server—so there is a significant environmental impact.

The information you are putting into this chat to ask a question can be used to train the large language model to answer other users' questions.

The large language model that trains accessible models like Chat GPT uses the entirety of the internet. This can lead to false information and/or unintentional biases (racism, sexism, ageism, ableism, etc.).

Most media literate readers can spot AI’s writing.

Writing is Hard. Grab Some Training Wheels!

Despite what some poets may say, writing doesn’t come naturally to most people. It is a skill that you have to develop through study and practice. English is full of inane idiosyncrasies, so think of AI as your free writing tutor— a grammar and craft know-it-all that is happy to correct you at any time. Additionally, AI can give you introductory advice on how to improve the quality of your writing.

The most obvious use for AI in writing is checking grammar and mechanics. I recommend using programs that are designed specifically for that because chatbots are not very good at taking and changing long blocks of text. They can give you general feedback but cannot replace an editor!

I’m sure most of us already know, love, and appreciate Grammarly, so now for the good stuff: How can AI help me while I’m writing?

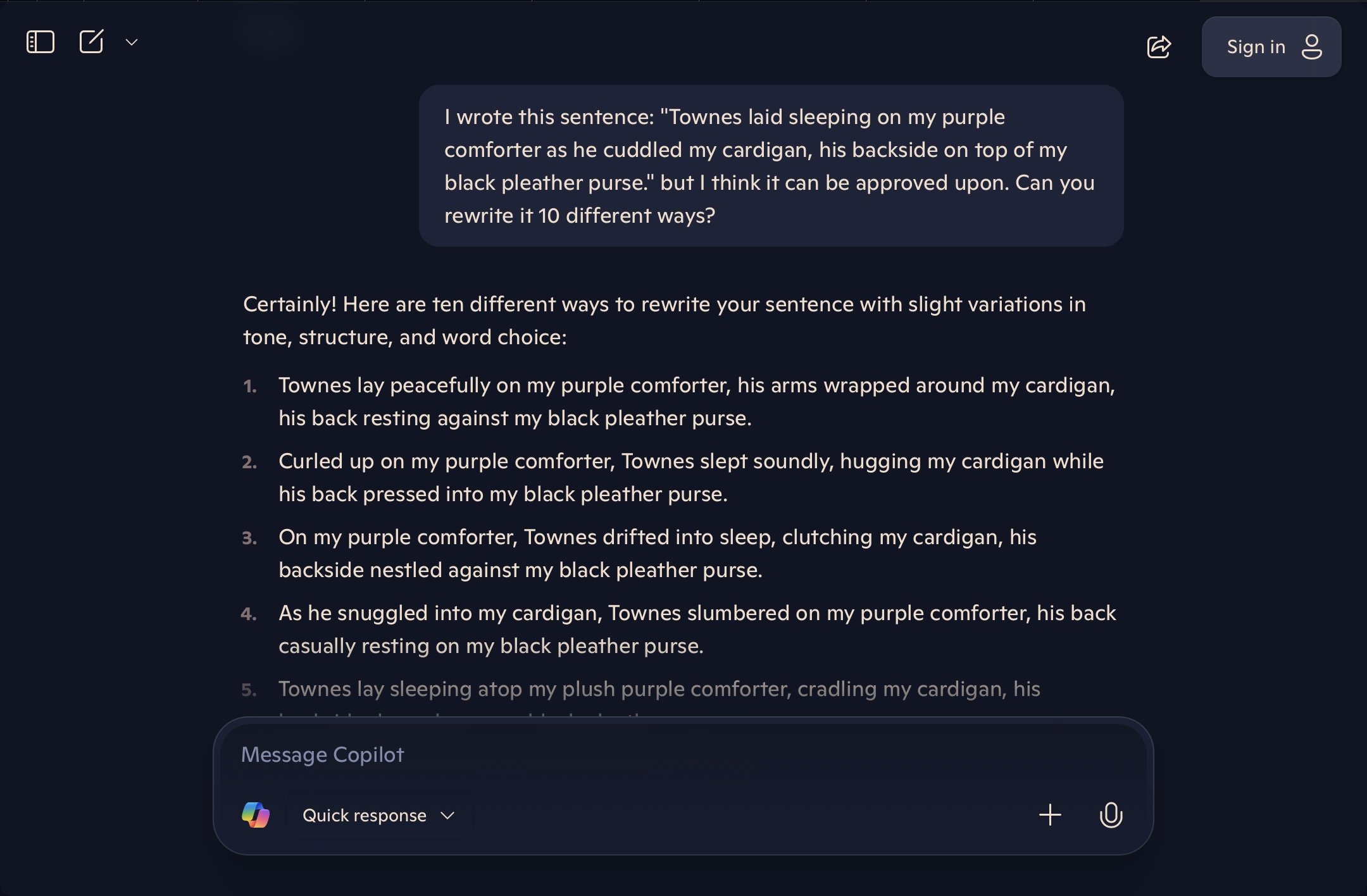

When it comes to drafting, the best quality of AI is that it can do a lot of grunt work really quickly. For example, take a look at this sentence I wrote:

“Townes laid sleeping on my purple comforter as he cuddled my cardigan, his backside on top of my black pleather purse.”

Now, there’s a lot I don’t particularly like about this sentence, but I’m not sure how I want to change it. Instead, I’ll see if my good friend Copilot has any bright ideas.

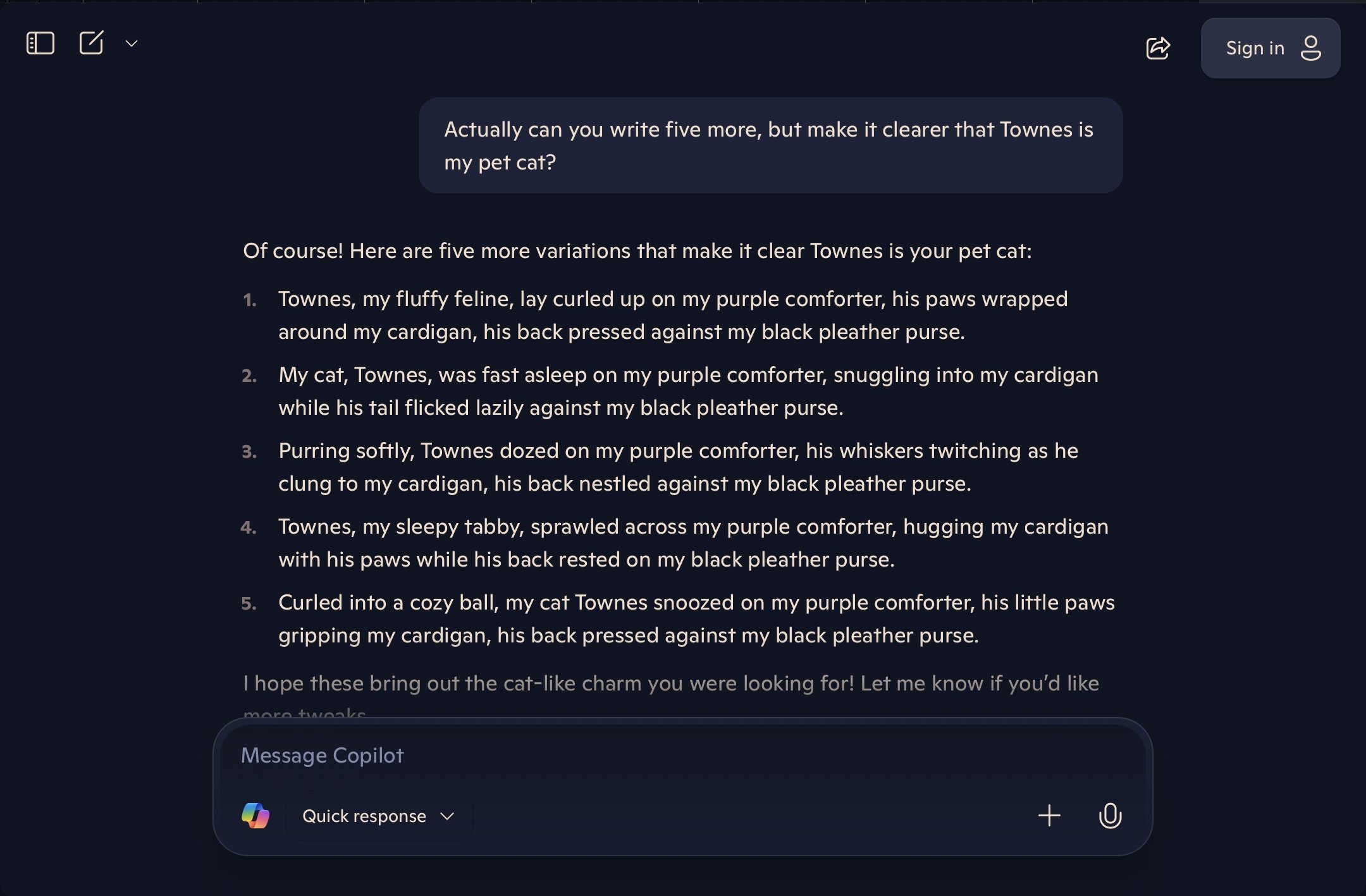

I showed the AI the sentence that I wrote, but I didn’t make it very clear what I was unhappy about. Let’s try again:

Now I have around 15 versions of this sentence with different descriptors and details, but none of them quite feel like my voice. To remedy this, I’ll combine a few that I really like:

”Townes, the ever purring Maine Coon, lay fast asleep against my plush purple comforter, his paws wrapped around my cardigan and his back pressed into my black pleather purse.”

Notice that there are certain details that the AI can’t accurately expand on, such as the exact breed of my cat or the quality of my comforter. However, AI can recommend synonyms, adjectives, or help you find that one word that’s just on the tip of your tongue. The more specific you make your request, the better.

A lot of word processors already have AI writing tools built into their software, but those tools simply offer suggestions. A chatbot, on the other hand, can help explain why your writing is too drawn out, not engaging, or at the wrong reading level. Understanding the “why” is what improves your skills as a writer.

As you’re reviewing your draft, AI can help you bulk up frail ideas or themes, adjust your tone to set a certain mood, and suggest structure or organizational styles. For example, if you’re working on a different type of project than you’re used to, you could ask the bot to give you an example outline. I always find it best to ask for several variations on answers, like I did with my cat query.

In fact, when I asked my favorite chatbot, Copilot, what it could do for my writing, it responded, “Think of me as an editorial guide rather than a ghostwriter—I help shape your words rather than replace them.” (By the way, this is not a plug for Copilot–I just like that it’s free, big, and links its information to real websites.)

Creative Projects

One thing most creative writers have in common is that you can find really weird stuff in our search history. Now AI can answer all of those strange hypothetical questions for you! It can explain how someone with certain psychological conditions might react to an event, or how someone with a rare ailment might be cured. I remember one of the first fiction writer questions I had to ask the internet was, “If you hit someone over the head, how long would they be unconscious for?” I’m glad my parents never found that in my search history. They would have been very concerned.

The good news is, you no longer have to turn to weird subreddits or Quora, because AI can probably tell you the answer. However, I recommend fact-checking most of what it tells you, which is why any AI that links its sources (like Copilot) is preferable.

If you need a setting, have your AI list out five different environments and see if any of those spark an idea. From there, the chatbot could tell you what animals live in those habitats, what adaptations humans would have to survive in those habitats, or what kind of weather would be the most common. At this point, you could probably turn to the internet, and return to your AI conversation whenever Google fails to answer the more niche queries.

If you don’t know where to start your creative writing project, AI can remind you what elements you need to consider. Tell your chatbot about what you’re writing and what your concerns are. It can give you an itemized list of ideas for a solution, but it’s up to you to apply them effectively.

Throughout this process, it’s important to remember that writing is supposed to be hard. Practicing creativity is important, so try to use AI as a moving walkway rather than a crutch for idea generation.

Final Thoughts

There is a certain book—I won’t say the title—rounding out some best sellers lists, that I am convinced was at least partially written by AI. I refuse to read it after reading several reviews that describe the extremely generic world building and passages that eerily resemble other popular books. However, the book is popular online because it is an echo chamber of its genre, and there are many young readers who cannot yet discern the unoriginality of this story within the genre.

I don’t know for a fact whether this author used any AI to generate their writing, but the book's existence paints a grim picture of what the future of literature will look like if we let AI do the writing.

Let’s think of literature as we do the Met Gala red carpet. When you’re writing, you want your product to be like Zendaya or Bad Bunny. Your book is unique to you and stands out while still fitting within the theme or genre you’re writing in. You might make stylistic choices that remind us of other books or even add small accessories that reference specific icons, but the outfit altogether is distinct, and how you wear it makes it yours. You could ask AI to help you come up with color combinations or explain the theme in more detail, but if it designs the outfit for you, you’ll be a black suit with a fun pocket square that you threw in for a pop of color.

As writers continue to experiment with AI, I want to encourage you to not let robotic writing outputs make you self-conscious of imperfections in your own writing. When we write, we make mistakes, and that’s OK. Comparing your first draft to AI’s writing would be like comparing Michelangelo’s “David” to a mannequin. One of them is cleaner, more uniform, and made faster, but no one is lining up to see a mannequin.