I recently read a post on Facebook from an author friend. She shared some unexpected news: someone had immortalized her on Wikipedia. The author in question wrote how it felt kind of odd to read the entry.

I had never really considered what reading about myself on Wikipedia would be like until I saw her status update. I imagine it opens up a whole host of conflicting emotions.

And I had to admit that I desire a Wikipedia entry of my own. I know it’s silly and vain of me, but I’m not going to lie. Achieving Wikipedia status appeals to that basic human need in me to leave a mark on this world. Even if it’s a tiny little virtual scratch.

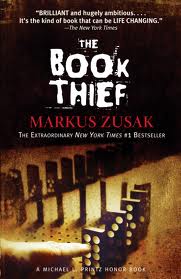

Wikipedia justifiably generates many detractors because it is crowdsourced. But it’s precisely Wikipedia’s neo-populist model that makes it a useful indicator for a writer, or any artist, who has decided to create for public consumption. A Wikipedia entry carries an implied proof that at least one person reacted strongly enough to an artist’s creation (in my friend’s case, it was a novel) to go to Wikipedia and generate a new page. Further, other people have agreed with the first person’s assessment enough to add to the entry and link to it. It’s validating to be immortalized in what has become the world’s encyclopedia.

But, unlike a traditional encyclopedia, Wikipedia presents a whole host of ethical dilemmas:

Is it okay for the subject of an entry to go in and edit his or her own page? Can an unknown like me bypass the work legitimate notability requires by simply starting my own entry? What differentiates justifiable, healthy self-promotion from crass, cynical manipulation of the crowdsourcing format?

Having the ability to edit one’s own encyclopedia entry is a can of moral worms, but, truth be told, I worry my biggest problem would be curtailing the amount of time I spent going to my entry to see if anyone had changed it.

Actually that’s not the worst possibility.

What if my hypothetical Wikipedia entry died an “orphan,” without any articles linked to it? What if I never met Wikipedia’s minimum “notability guidelines?”

What happens at that point? Do the Wiki gatekeepers just remove you at three a.m. when no one’s looking?

How horrible! You get up in the morning and go to check on your little Wiki-corner of the world, but it’s gone. Erased from the Wiki world.

That kind of rebuff might prove too much for the flimsy structure that is my writer’s ego.

Maybe my lack of “success” is a good thing. At least at this point. Maybe I’m not quite ready to be carved into the heights of Mt. Wiki. Maybe I need more time and experience to toughen myself up. Maybe joining the world’s gallery of notable names might be too stressful for me, at least at this point in my career.

Maybe instead of wasting my imagination on these monumentally hypothetical musings, I should try to keep myself focused on more concrete, immediate goals like finishing this short story I’ve been stuck on for a couple of weeks.

Hmm, I think I might be onto something.